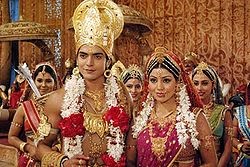

But popular mobilisation was allowed to settle a juridical issue, and that shifted the terms by which the issue was judged thereafter. The m asjid was called disputed property, but in fact, its legal ownership was not in question. The demolition was an inflection point thereafter Hindi news never looked back and gained more and more influence. The television show lent the movement generous helpings of legitimacy and faith among the Hindu public and marked a crucial flashpoint in Indian politics.īroadly, the English news coverage saw the Ramjanmabhumi campaign as a threat to law and order, while the Hindi press was open to the religious claims being made and often saw the movement as reflecting majority sensibility. Simultaneously, the growth of the televisual medium also coincided with a landmark media event that inadvertently energised the janmabhoomi movement: the weekly broadcast of the serialised version of the Ramayan, a soap opera based on the Hindu epic of the same name, on state television. In the years leading to the demolition of the Babri masjid (mosque) in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, the sociopolitical fabric of India was undergoing a sea change that was led in part by the growing prominence of the television in India.Īs TV sets became commonplace in every Indian household, coverage of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement (the movement to restore the birthplace of the Hindu deity, Ram by demolishing the Babri masjid and building a temple in its place) reached Indians across the country in an unprecedented way.

The Hindu nationalist movement had long been on the fringes of the Indian polity in the years following independence, but had not yet found its way into the mainstream. In his book, Politics after Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India, NYU media scholar Arvind Rajagopal explores the role played by emerging communications technology in Indian politics during the 1980s.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)